Welcome to the Computer Vision and Multimedia Lab website.

Welcome to the Computer Vision and Multimedia Lab website.

GET IN TOUCH

Tactile image of the painting "Christ and the Samaritan woman" / Didascalia tattile del dipinto "Cristo e la Samaritana"

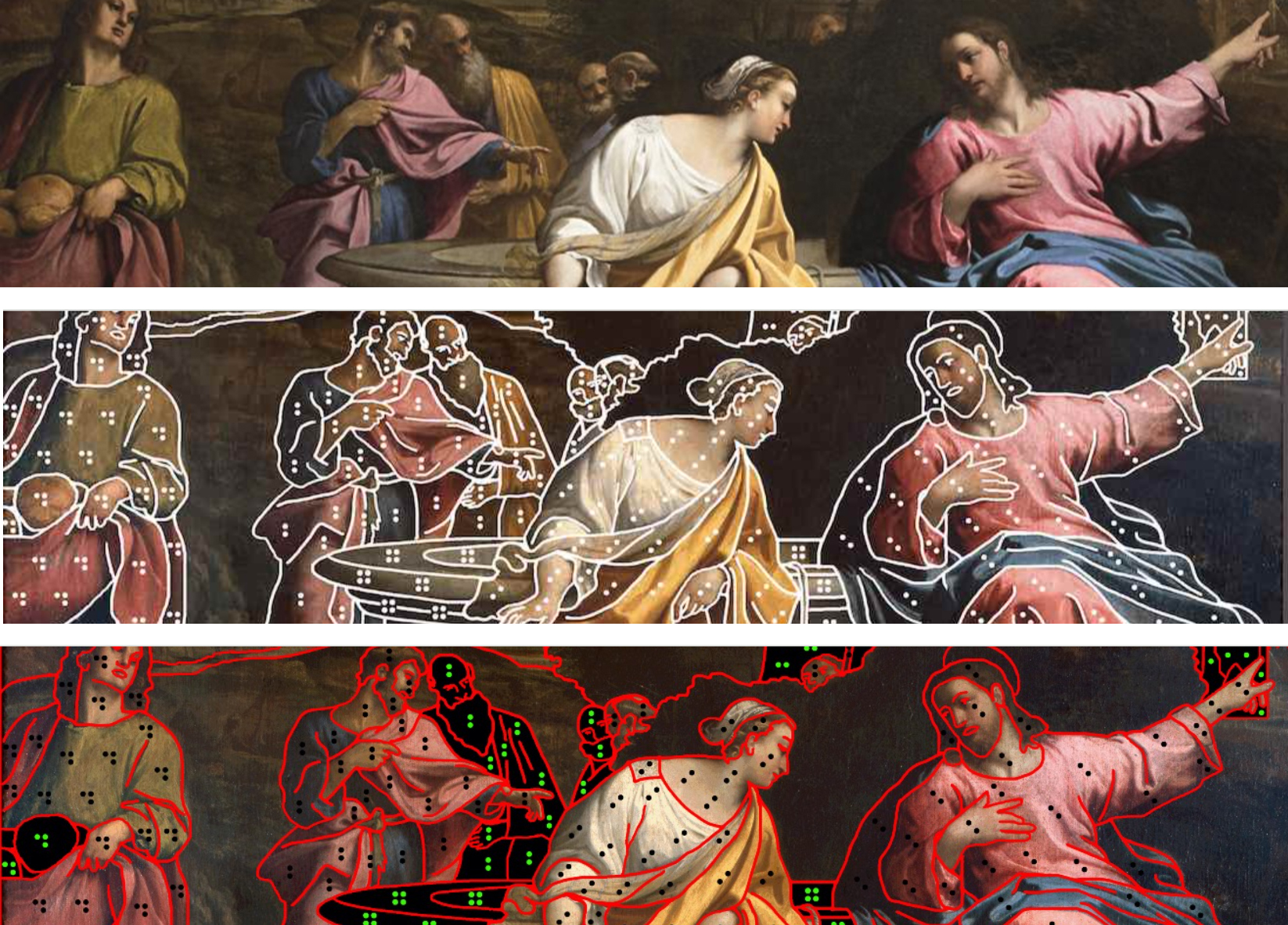

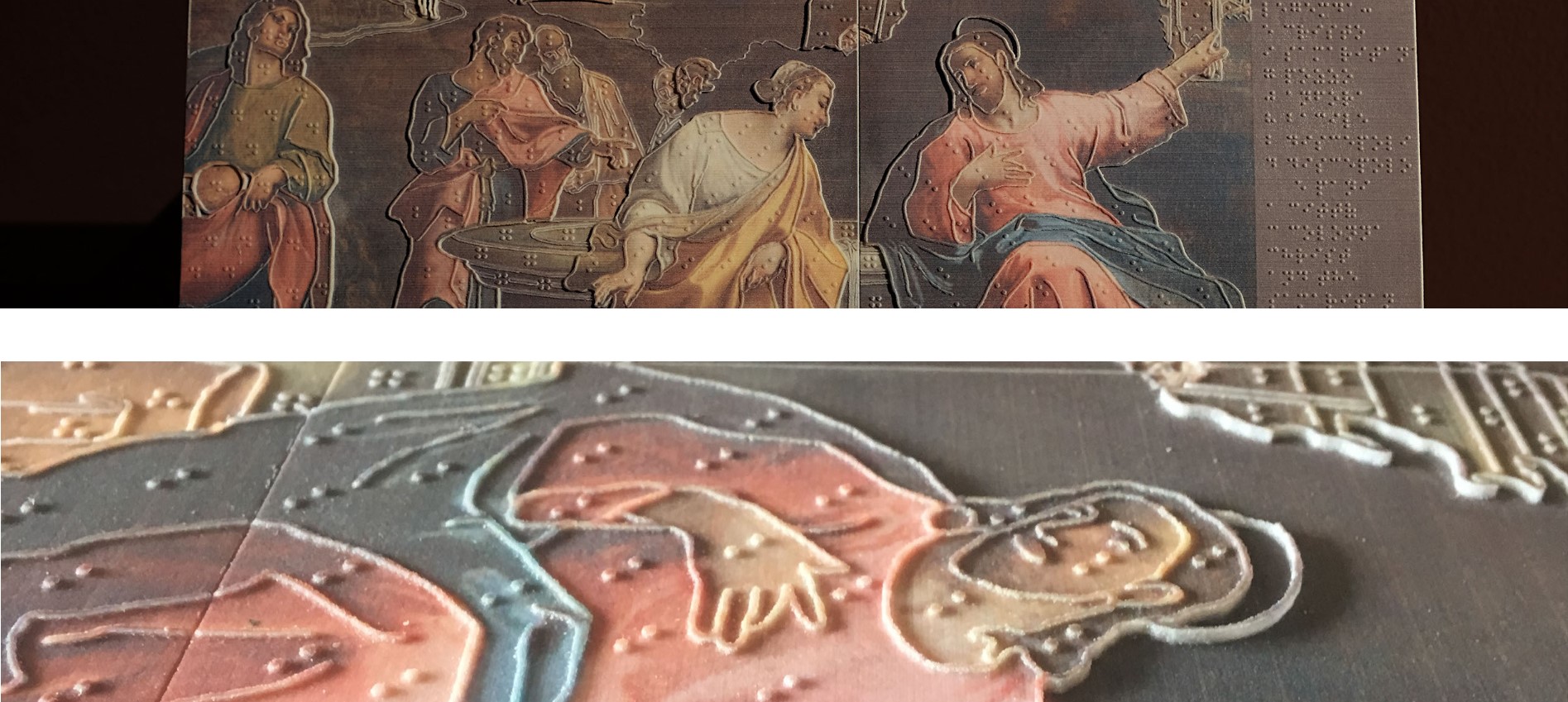

The tactile image of Christ and the Samaritan woman, a 1593-1594 oil on canvas painting by Annibale Carracci, was made in 2016, in collaboration with the Institut of Information and Communication Technologies of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences and the staff of the Educational Services of the Pinacoteca of Brera. It is located, beside the original artwork, at the Pinacoteca of Brera in Milan (Italy), in Room XXVIII.

It was shown the first time on the 9th of November 2016 to associations and organizations of blind and low vision people.

The 3D printing of a tactile version of the painting, with the dimensions of an A3 sheet (29,7 x 42 cm), has been shown in the occasion of the exhibition "L'epoca fragile [The fragile era]?" (30 November - 15 December 2024), at the Diocesan Museum of Pavia, in early December 2024. It has been part of the installation on fragility, with the aim of making a painting accessible even to visually impaired and blind people, reproducing an haptic version. It has also been the focus of a disability debate (Friday, 6 December 2024), with guests from the Italian Union of Blind and Partially Sighted people (UICI) and the Italian Union for the Fight against Muscular Dystrophy (UILDM). The tactile version has been designed by the Computer Vision & Multimedia Lab (CVML) of the University of Pavia and printed at the Institute of Information and Communication Technologies of the Bulgarian Academy (under the supervision of prof. Virginio Cantoni, the support of the Lombardia Regional Council UICI chaired by Nicola Stilla, and the collaboration of the Collegio Nuovo of Pavia).

How can visually impaired people to get what a painting depicts?

There are numerous methods for making a painting accessible to the blind, and nearly all of them use haptic perception, that is the process of recognising objects through touch. To perceive an object’s shape, material, placement in space, and texture, those who are blind or visually impaired need to touch it. But how to translate what is represented in a painting in a way that can be read through fingers?

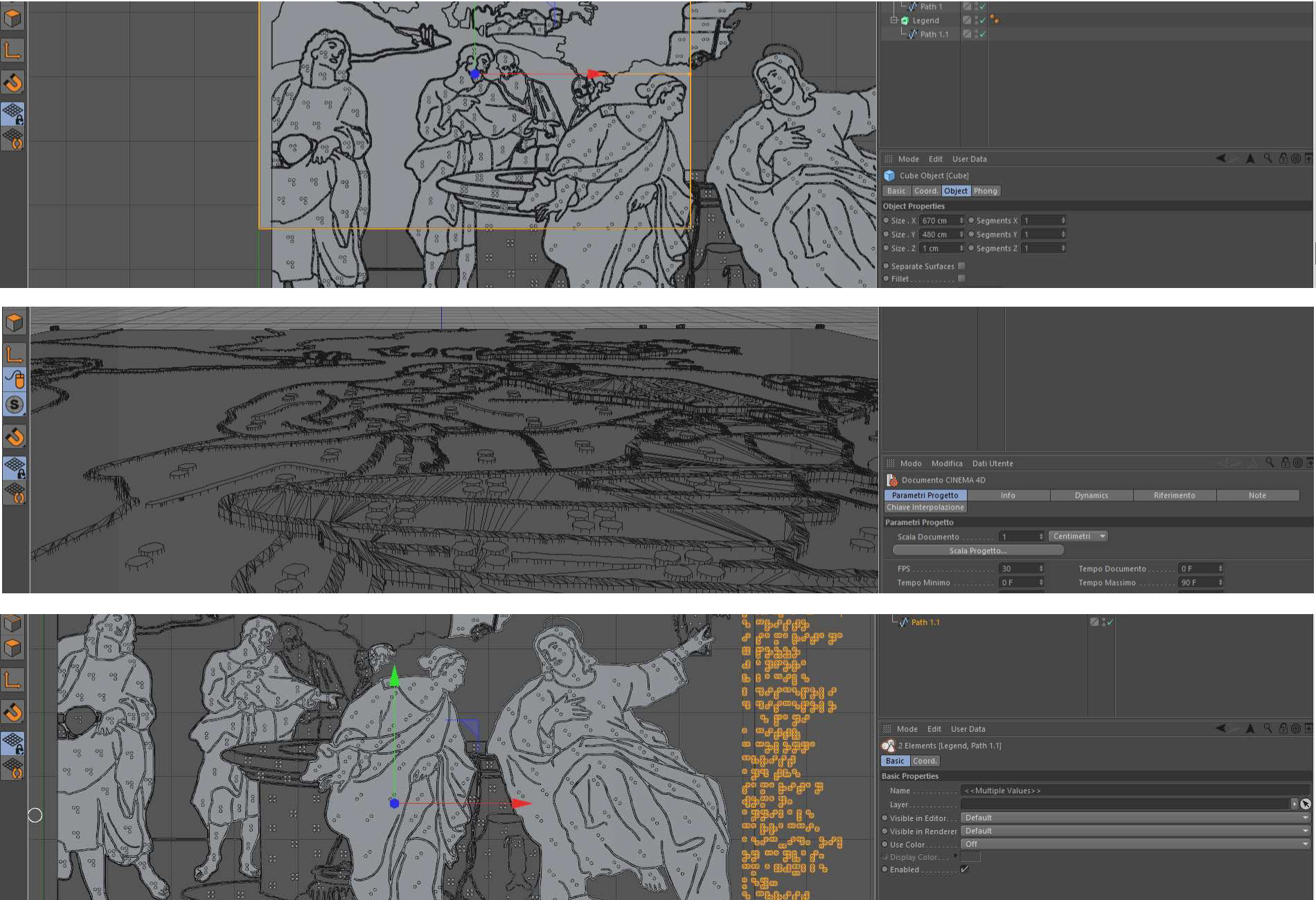

From 2D to 3D

The literature offers a number of ideas for turning a 2D image into a 3D relief, but it's yet unclear which tactile translation is best. As a result, there are currently no universal standards, and the guidelines that do exist are typically addressed to specific situations that take advantage of 3D printers to transform images into touch-explorable products. Colour can also be utilised to give additional information to partly visually impaired.

Blind people's residual visual capability varies depending on their experience, ranging from those who are born blind and totally lack visual experience to those who develop blindness later in life, and those who are visually impaired in different degenerative forms.

Since its initial presentation in November 2016, the tactile caption shown here has been well appreciated. Several associations have been consulted in order to develop this and other accessibility approaches. This solution, which is still in use in Pinacoteca di Brera room 28, is based on morphological primitives that may be recognised through relief outlines and mnemonic coding based on the Braille alphabet.

The tale, the painting's composition, the animated and inanimate characters, and information on spatial depth—which may be identified in the picture by comparing the relative sizes of its components—are all described in a Braille text. Depending on the tactile point in question, depth and distances can also be vocally conveyed and described.

The painting's objects and figures have been selected based on the composition's semantics, and the contours that have been found are depicted using a very small number of layers to allow for the perception of heights by touch. As a result, the tactile caption contains varying height components. In certain places, the figures are empty, with only the contours in relief; in other places, the figures are full, as in the case of Christ and the Samaritan and all of the image's important figures. The edges of these figures are similarly elevated.

It was encouraging to find that even those with very limited visual experience may benefit from the suggested method, even though not all blind or partially sighted people have the same tactile exploring ability.

At the inauguration

Virginio Cantoni (CVMLab, University of Pavia - leader of the project); Associazione ARTE INSIEME Onlus Volontari per l'arte; Ageranvi, associazione genitori ragazzi non vedenti; UICI - unione nazionale ciechi, con UICI Lombardia, UICI Monza e Brianza e UICI Varese; Associazione Nazionale Subvedenti onlus; Istituto dei ciechi di Milano; experts in museum accessibility design.